Names in Arabic

I’m going to start this section with a disclaimer: I do not speak Arabic. I am going to do my best with pronunciations, but I am 100% open to corrections and I apologize in advance if I butcher a name.

Ok, having said that, Arabic names, especially historical Arabic names, can seem intimidating to those not familiar with the naming customs of the time. So I want to talk a little bit about what goes into the names that we are going to encounter in this and other upcoming seasons of the podcast. This breakdown is going to apply to the historical names of Muslim Spain above all – modern day Arabic names are often put together differently depending on the country of origin of the person.

We’re going to use our first Muslim governor’s name as an example: Musa ibn Nusayr al-Lakhmi. So the first name we have is the given name, basically what his parents named him, and that is Musa. It’s similar to how your given name is Peter and mine is Sarah. Often Arabic names are just regular nouns or adjectives and have meaning – Musa means “of the water” and is related to the name Moses. Because Arabic names are regular words with meaning, they often have prefixes – Abd or Abdul is a common prefix meaning “servant of”, so the name “Abd Allah” means “servant of God”. Second or middle given names were not common at this time, although they are in modern times.

The second part of an Arabic name is the patronymic. This is something you see in other cultures as well – think of Russian names that have a given name and then a second name ending in -ovich or -ovna which means “son/daughter of”. So if your father was Konstantin, your patronymic would be Konstantinovich or Konstantinovna. It’s based on the father’s given name. Well, Arabic names of the time function the same; the second part of an Arabic name begins with “ibn”, meaning “son of”, and then the father’s given name is listed. So in the case of Musa, the second part of his name is “ibn Nusayr”, meaning “son of Nusayr”. If you had a really important grandfather, you might have two “ibn”s to include both your father and grandfather, but this isn’t common. If you’re a woman, you use the word “bint” instead of “ibn”.

The last part of a name is what English speakers are used to as a family name, but the final name is not always family-related in Arabic names of the time. In Musa’s case, the final part of his name is “al-Lakhmi”, which refers to the Lakhmid kingdom of Southern Iraq and indicates that he was probably a part of that clan. So in this case, Musa’s “last” name does indicate family or tribal affiliation, but it doesn’t always. It can indicate where a person is from, as in the name al-Baghdadi. It can also be like a nickname, as in the name al-Rasheed, meaning “the rightly guided”. Eventually these kinds of names became something that would be inherited from father to children, and so in modern times they do function like family names, but this won’t be the case with the names we see.

Names for people in Muslim Spain

Let’s start with some of the names for this new people we’re discussing. Muslim is pretty straightforward – it refers to the religion of this new empire. Caliphate is straightforward too – it refers to the empire itself, which is headed by a caliph.

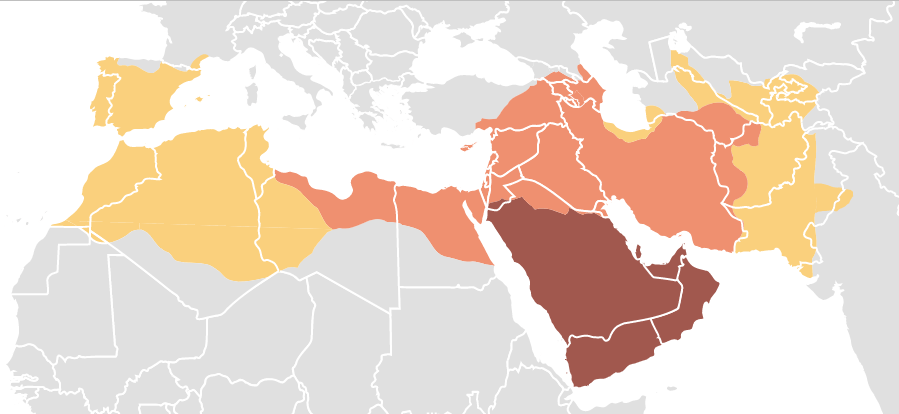

The new people arriving to Spain are often called Arabs – this refers to their ethnicity, as the conquerors originally came from the Arabian Peninsula. The designation “Arab” can also be broken down into smaller groupings; during the period of the governors we will be hearing about Yemenis and Syrians, for example, referring to people who come from specific places IN the Arabian Peninsula. However, you will also hear a lot about the Moors. Moor is a name that Christians will use to refer to the conquerors, which comes from the Roman name of the province of Mauritania. So basically, it means North Africans; the term of ethnicity for them is Berbers.

There are many ways to refer to people living in the Iberian Peninsula during this time, depending on whether they lived under Christian or Muslim rule and whether they had or had not converted to the dominant religion of their area. We’ll start with the Christian north. Jewish people were called Jewish if they hadn’t converted to Christianity and Conversos, meaning converts, if they had. Both groups faced persecution, as we have seen. Christians were just called Christians, or sometimes Old Christians, and they were the dominant power. Later during the Reconquest, there will be former Christians who had converted to Islam living in newly reconquered Christian territory. These people are called Renegados, meaning renegades or deniers. They will not be treated well. Muslims in Christian territory will be called Muslims (or Mudejars later on, this word means “subjugated/tamed”) if they hadn’t converted to Christianity, and New Christians (or later, Moriscos, coming from the word Moor) if they had.

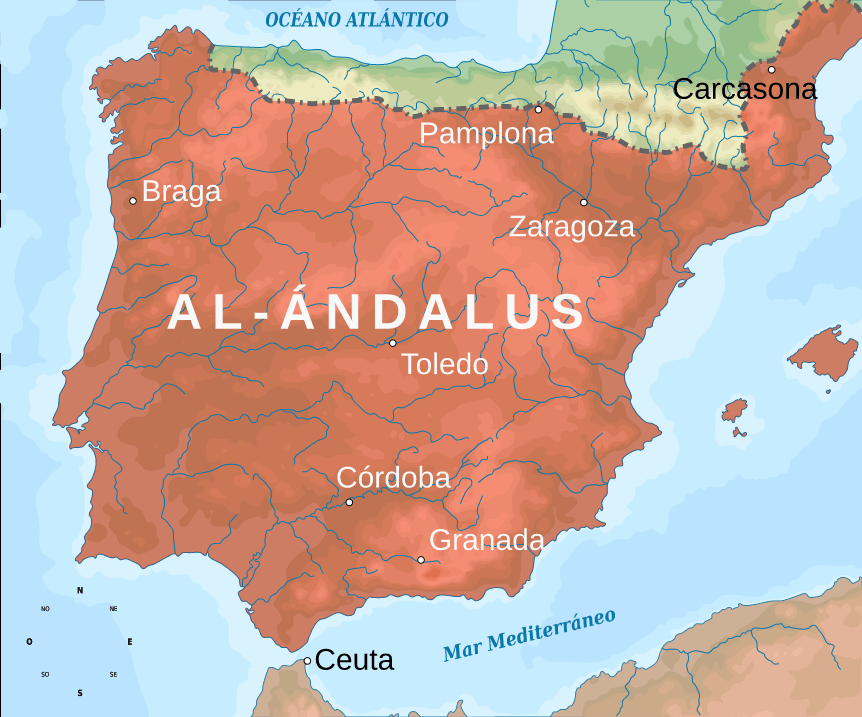

In Al-Andalus, which is the Muslim-controlled south, those who practiced the Jewish faith were called Jewish and those who practiced the Christian faith were called Christians or Mozarabs. These people were known as dhimmi, or people of the book, and as such were protected under Islamic law, although they had to pay an extra tax. People from either of these groups who did convert to Islam were known as Muwallad or Muladí, meaning a person of mixed ancestry or a non-Arab Muslim.

What about the name al-Andalus?

??????

The Map